Notes on Maputo

I spent the month of October in Maputo, Mozambique. I didn’t leave the city other than day trips into the neighboring city of Matola, a boat trip out to Inhaca Island, and a trip across the tallest bridge in Africa and back.

Maputo is a very pleasant city. It’s easy to get around, very cheap, very safe, and quite fun. I’ve previously lived in Sierra Leone and Gambia, but Maputo feels much more like Mexico City than either of those.

This post is about the city. I don’t think there’s ever going to be much tourism demand for Maputo. It’s very far away for European and American tourists; most of them are going to end up in Cape Town. But it’s an interesting Place, with an interesting history and current political and social climate.1

History of Maputo

My sources: The best history of Mozambique is Malyn Newitt’s 2017 Short History of Mozambique, an abridged version of his much larger 1995 History of Mozambique. I also found the Marine Corps Intelligence Agency’s country study on Mozambique useful. My understanding is that the MCIA produces these 300-400 page books on every country in the world for the embassy guards, and there’s a correspondingly useful focus on cultural norms, good places to eat, and the inadequacy of the Mozambican Navy.

Maputo sits at the mouth of the 50-mile wide Maputo Bay, into which four rivers empty from the Swazi and South African highlands. There are no primary sources for Mozambican history before the 16th century, and few for Maputo until the 18th century.2 Portuguese explorers landed briefly in 1502 and 1544, but mosquitoes drove them off. The city is on a great fishing spot, so there were numerous Bantu fishing villages around, but historians don’t know much about their lives, and none of these sources speculate. In the 18th century, Maputo cycled through Dutch (trading ivory and slaves, losing money, driven off by a local tribe), British (passing by on their way to India), Austrian (the Holy Roman Empire built two forts; again, ivory and slaves), and back to Portuguese hands in 1781.

Drought is the constant worry of southern Mozambique. The Portuguese history of Maputo is detailed from the 1780s, and in 1795 drought struck the colony. During this first recorded drought, the French attacked the Portuguese colony, and occupied it. The Portuguese returned for good in 1799.

How rough was Portuguese colonial rule in Mozambique? I’d say worse than the British or French in West Africa, not as bad as the Belgians or Germans, and about the same as the British in East Africa. Most importantly, Mozambique was the primary supplier of slaves to Brazil and Cuba. Newitt estimates that more than 2.5 million slaves left Mozambican ports for the Americas between 1800 and 1850. Most of the early exploitation (until around the 1890s) was on the coast well north of Maputo.

It wasn’t until the British began moving north from their South African colonies that Portugal really focused on Maputo and the south. There was an indigenous state on the coast north of Maputo, the Gaza Empire. Newitt:

The continued existence of a powerful and independent African state weakened Portuguese authority vis à vis the African population in the south and cast doubts on Portugal’s ability to control its colony in the opinion of the watchful British and Germans. Moreover, the Portuguese wanted to open up the area of the Gaza Kingdom for labour recruitment. Early in 1895 the new High Commissioner, António Ennes, decided to force a showdown with [Gaza Emperor] Gungunhana. A large expedition was sent from Portugal supported by gunboats, cavalry and machine guns and in a rapid and decisive military campaign Gungunhana’s regiments were defeated and the king himself captured.

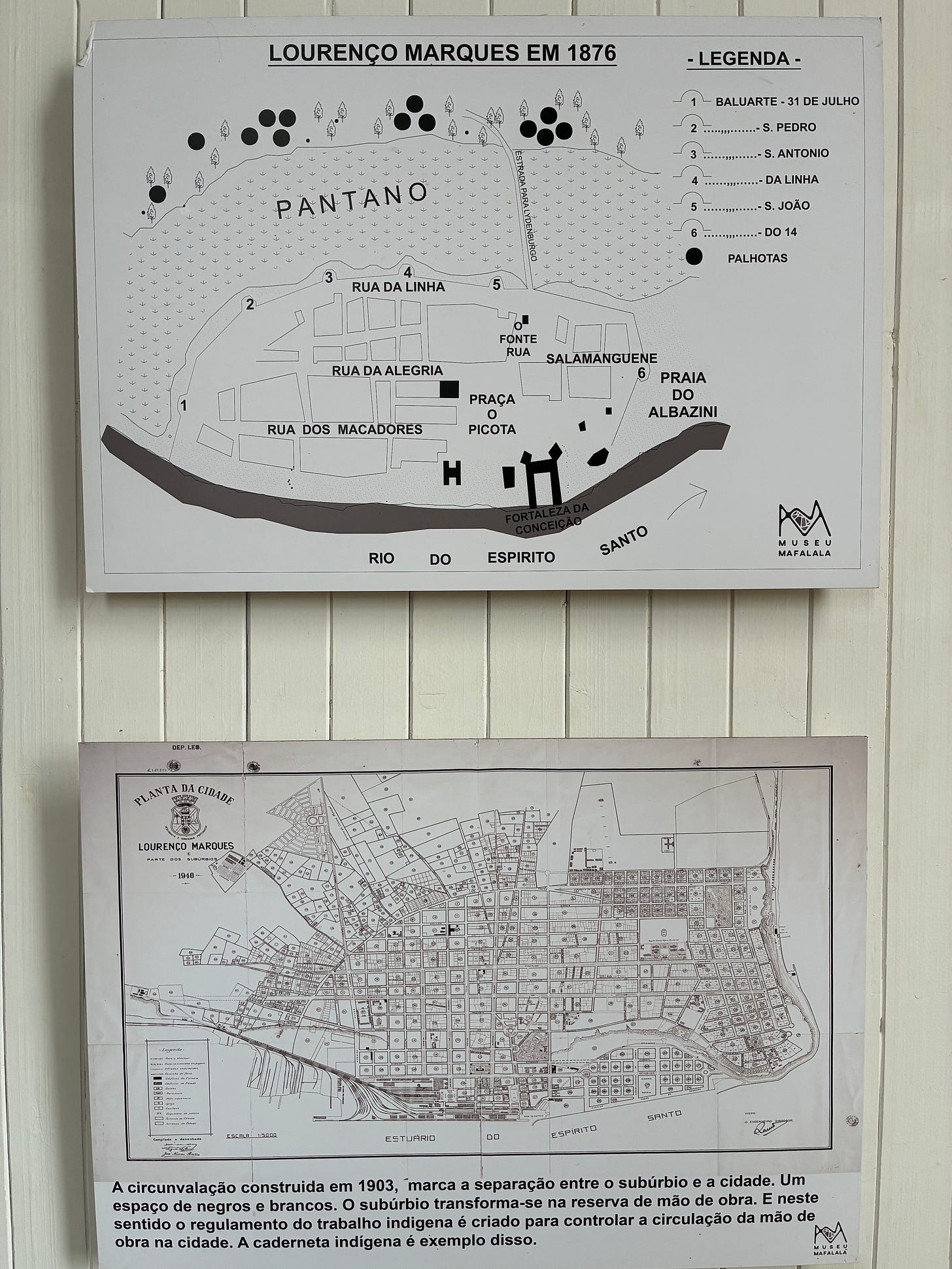

Three years later, the capital was moved from Mozambique Island, 1,000 km to the north, to Maputo. It was at this point that the central city took its current shape:

The swamps were filled in, connecting the low city with the higher bluffs, and a grid was laid out. The new capital took administrative focus away from the north; while the slave trade was 50 years dead, there was still intense labor exploitation in mining, railway construction, and agriculture. The south saw a relative growth in industry and trade.

Portugal maintained its own form of apartheid in its colonies through the 20th century. The central part of Maputo was de facto white-only. While black Mozambicans could acquire “assimilated” status, “Very few Mozambicans went through the difficult process of acquiring … assimilado and those who did were usually closely connected to the regime.” There was also forced labor through the chibalo system, through the 1960s. For any crime (Newitt highlights tax arrears, “inappropriate dress”, and “indolence”), black Mozambicans could be sentenced to penal labor, or sent to São Tomé or Macau. The police who enforced these laws were black, and were also recruited through compulsion and press-gang raids. There was substantial voluntary and involuntary migration to the mines in the South African Rand.

Mozambique’s war for independence escalated gradually from 1964, and was almost entirely a rural affair. Much like the current ISIS problem in the northernmost province of Cabo Delgado, the guerrillas operated from Tanzania. Maputo and the other major city, Beira, were untouched, but isolated. This is because the country was heavily rural: less than 20% of the country’s population at independence lived in any sort of town. The Portuguese took the war very seriously. Their operations in Angola and Mozambique wrote the doctrine for late-century counter-insurgency. They fielded large Africanised units, and mostly won both the Angolan and Mozambican wars in 1970. FRELIMO (more on them below) attempted to open new fronts in 1973, but it was mostly too late by then. Events in Portugal ended the war for independence permanently.

Portugal was the last of the European states to grant its colonies independence, but they couldn’t hold out any longer. The dictatorial government of Portugal was overthrown in a 1974 coup; the new government put a sudden end to the colonial wars in Angola, Guinea-Bissau, and Mozambique by granting them independence.3 The war of independence in Mozambique, which had been stagnating, immediately turned into a civil war between FRELIMO and RENAMO.

FRELIMO is a pretty straightforward 20th century Marxist-Leninist independence movement cum developmentalist single-party rule. It was founded in Tanzania in 1962 with support from Julius Nyerere and of course, Newitt notes, “suspicions had been aroused that the CIA had been involved.” FRELIMO, as the most prominent of the guerrillas at independence, was handed the government by default; their president at the time, Samora Machel, became president of the country.

There had been no popular insurrection and the most populous parts of the country (the provinces of Zambesia and Mozambique) had seen little fighting. Frelimo had not tried, and had certainly not succeeded, to mobilise the population or to establish itself in any of the main towns.

In the first year after independence, “most (possibly 90 per cent) of the population of European origin left the country.” FRELIMO had been established as a Marxist-Leninist movement, and cooperantes from Eastern Bloc countries began to fill in the gaps. They also seized most industry and established a command economy.

RENAMO is more complicated and no one will give me a straight answer. It was definitely founded and supported by white Rhodesian and South African intelligence agencies. During the war of independence, FRELIMO had developed strong ties to the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU), which was fighting against white-minority rule in Rhodesia. After independence, FRELIMO continued support to ZANU, and the Rhodesians didn’t like that. This was the beginning of what Gerard Prunier calls “Africa’s World War”: at the same time, South Africa invaded Angola, further destabilizing it right after its independence. The broader conflict spread throughout southern Africa, and there’s a line of continuity to the conflict in the eastern DRC today. Back in 1976, according to Newitt, “the first sign” Mozambique would be drawn in was “the formation by the Rhodesian intelligence service of an armed guerrilla force to carry out sabotage inside Mozambique,” while “Rhodesian forces carried out major raids on the ZANU camps” within Mozambique.

It almost ended there, with the change to black rule in Zimbabwe in 1979. Of course, the South Africans couldn’t let it be, and took over training and funding the anti-FRELIMO militants. Around this time, RENAMO became the predominant anti-FRELIMO group. This is where I lose track of the civil war. Newitt writes: “It is not clear that the Renamo leaders and their South African backers actually wanted to achieve the overthrow of the Frelimo regime.” So... what did they want? South Africa was definitely opposed to any country ruled by blacks which would help the ANC or SWAPO, but didn’t seem to have any end goals than to sow chaos. As best I can tell, since its founding RENAMO has defined itself as a “FRELIMO-bad” movement.

It was a bad civil war, as these things go.

During the fighting Renamo employed methods that were at that time relatively uncommon. Children were kidnapped to become soldiers and were forced to carry out killings. Rape and the mutilation of civilian captives was widely practised and people were also enslaved to provide Renamo with a work force. Such methods were to become all too common in wars throughout Africa in the following decades but some writers have seen in this behaviour a continuity with the pre-colonial past where much of Mozambique had been subject to warlords and their violent enslavement and exploitation of the population.

Oddly, Newitt quotes, “Renamo must have been the only so-called anti-communist guerrilla force which Washington did not actively support.” My guess is that DC had helped found FRELIMO, and felt silly flip-flopping within a decade. Or they just weren’t pay much attention to Mozambique.

The civil war petered out in 1992. FRELIMO had started to move away from its Marxist roots in 1983, and completely gave up on Marxist-Leninism at its fifth party congress in 1989. This had been one of RENAMO’s major demands, and both parties started seeing a route to normal politics. Everyone was exhausted by the war.

Throughout and since the civil war, FRELIMO was dominant in Maputo and the south of Mozambique. My sense is that, after the mass exodus of Europeans after independence, Maputo was a ghost town and quickly FRELIMO established its socialist command economy of the 70s and 80s there. This is why all the street signs look like this:

Aid flowed into the country after the civil war and the de-socializing. The rebuilding and investment were strongly focused on Maputo, and FRELIMO benefited far more than RENAMO, which was now acting like a totally normal political party that hadn’t done any war crimes. Some notable investments were an aluminum plant in Maputo which consumed 45% of all Mozambique’s electricity and several hydro dams to power the smelter. Since the end of the war, Maputo has been the social, political, and economic center of Mozambique.

Recent history

FRELIMO continues to hold the presidency, 70% of the legislature, all governorships, and the mayorship of Maputo. RENAMO holds a few other mayorships and seats in the legislature, but hasn’t seriously contested the presidency since 2014.

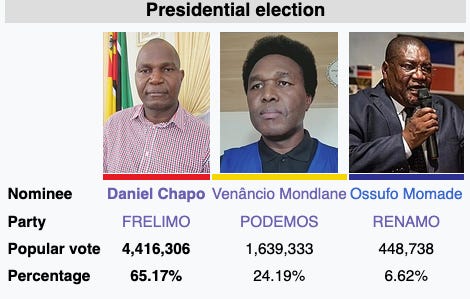

The most recent election was the 2024 national election. The FRELIMO presidential candidate, Daniel Chapo, won with a reported two-thirds of the vote. The runner-up was Venâncio Mondlane, a populist candidate who had left RENAMO for PODEMOS,4 which had been founded by a splinter of FRELIMO in 2019.

The official results reported that Chapo won 65% of the vote and Mondlane won 25%. Almost everyone I talked to in Maputo thinks that Mondlane actually won, and FRELIMO just did a really good job of fixing the election. Surprisingly, the more connected to the current government someone was, the more willing they were to admit these suspicions. Yango drivers and one particularly passionate fisherman were the only people who told me they thought Chapo had actually won the election. PODEMOS’ popularity was strongly concentrated in urban areas, regardless of region, which probably contributes to the bias of my sample.

After the 2024 elections, there were large and deadly protests on behalf of Mondlane and PODEMOS in major cities. The first 2-3 months after the election saw 100+ deaths during protests, and Mondlane fled to South Africa at least twice. Mondlane and Chapo met in person earlier this year, and Mondlane has since founded a new party, ANAMALALA.5

There weren’t any protests while I was in Maputo. At this point, people’s suspicions are mostly resigned; no one told me that they thought Mondlane would have been a better president anyway. More often I’d hear that they wanted a change after 50 years of FRELIMO rule. One topic which came up a lot was the high compensation for government workers, mostly in benefits rather than salaries. This was prompted by the IMF noticing that the government was spending 60% more on salaries than expected in 2023, and requested that the government reduce their bureaucratic wage-to-GDP ratio to under 10% (!!).6 Chapo promised to do this (in English), but also promised (in Portuguese) not to make any wage cuts. Government workers are upset about this, local policy wonks are upset about this, other Mozambicans assume all government wages are just rent-seeking.

How poor is Mozambique?

Mozambique makes the bottom of a lot of lists of development indicators, and that felt subjectively wrong to me. Ken Opalo recently shared this graph:

In public health, Mozambique is bottom-10 in malaria, HIV, TB, maternal mortality. Maputo is definitely an African city, but there’s a visible middle class, and not a visibly high disease burden.

I lived in Sierra Leone for a year. Most of that time was in the capital Freetown, but I also spent four months on the road, visiting every district in the country. Sierra Leone felt much poorer than Mozambique, despite having better economic indicators (GDP per capita, HDI, median income, GINI, etc.). Mozambique also feels richer than Gambia, which is twice as rich per capita! I think there are a few reasons why the stats don’t match the subjective feel of Mozambique.

First, I only visited the south of Mozambique, and mostly the urban area around Maputo and Matola. Mozambique is primarily an agricultural economy (about 85% of the workforce), and unlike Sierra Leone, a majority of farmers are subsistence farmers. The farms that I saw were relatively large and targeting the South African export market. The subsistence farmers are mostly in the north, out of my view.

The north sounds like a different world, and that’s why I called this “Notes on Maputo” instead of “Notes on Mozambique”. Besides the very different economy, the northernmost province, Cabo Delgado, also has a minor ISIS problem. There is no security threat in Maputo.

My urban/regional limit doesn’t explain most of the difference in city-feel though. I’ve never left urban Gambia, and the nicest areas of Maputo are much nicer than the nicest areas of Kanifing, and the worst areas of Maputo are slightly nicer than the worst areas of Kanifing. Again, GDP per capita and median income in Gambia are more than twice those of Mozambique.

A second and important factor is Mozambique’s relatively massive exports. Their exports make up 45% of GDP, compared to 20% in Sierra Leone and 7% in Gambia. Being right next to South Africa also helps.

Third, many Portuguese never left after the late decolonization, or have come back since the end of the civil war. This population creates strong demand for middle class amenities. Almost all of the expats in Freetown are on temporary postings, so fewer nice houses get built, less nice furniture is imported, and there’s less investment in communities. For expats in Freetown, a lot of the social life revolved around embassies. These are the institutions most worth investing in long-term. The social spaces, bars, gardens, restaurants are what made Maputo feel comparatively lively.

Finally, it’s really hard to count stuff in Africa, and all of the development indicators might just be wrong. Oliver Kim

and Adam Salisbury make the point well; statistics agencies are understaffed and have different incentives. This could have led to a systematic bias against Mozambique somehow. I don’t have a hypothesis of why this might be, but I am generally not very confident that these numbers are “right”.

A related point is that Mozambique is only at the bottom of lists of a subset of stable countries. If Nigeria’s economic statistics are mismeasured, then countries at war or without a functioning government certainly are doing worse. Afghanistan used to have the worst maternal mortality in the world, but not anymore! Once all the NGOs and aid agencies withdrew, there was no one to measure maternal deaths anymore, and the Taliban aren’t prioritizing it. During the American occupation, there was great data on health, and no government with the weight or incentive to pad those numbers. Even then, there was no convincing evidence that Afghanistan’s maternal mortality was worse than Somalia, Burkina Faso, or even Pakistan. It’s the same with Mozambique. If we had good data from Sudan or Somalia, they’d probably look substantially worse in comparison.

What’s Maputo like now?

Maputo is very green, and the streets are very wide. The old city, the parts built during early Portuguese colonialism, are on a neat grid. While the city is mostly flat, the 18th century part of the city, Maputo Baixa, sits at sea level, and Maputo Alta sits on bluffs about 50 meters above the oldest buildings.

There are also a lot of tall buildings. The central business district has several 20+ story offices, and there are many 10+ story residential buildings. This was really surprising! Freetown had only two buildings >10 stories when I was there. I think Mozambique’s skyscrapers exist because there is especially high demand for living in the old and white part of the city, even since independence. There is no equally desirable area in Freetown.

These incentives are lessening, especially since the big road to Matola (2019), the city to the west, and the bridge to Katembe (opened in 2020) were completed. Many wealthy Mozambicans now live in Matola, and on my trips to Katembe I saw dozens of very large and modern houses being built. I never saw a traffic jam, other than rush hour on the Matola road.

Maputo feels like a high-trust city, relative to other cities in Africa. Drivers follow traffic laws: there was strong adherence to traffic lights, which I haven’t seen anywhere in West Africa. Motorcyclists lane split, but with only a minor death wish. None of them wear helmets. I also didn’t see any difference in how nicer cars drive. The two equilibria I’ve seen are that nicer cars get pulled over more often, and therefore drive more carefully (Gambia), or they have tacit immunity and drive like it (Afghanistan). Even the President’s motorcade only took up one lane of traffic.

High trust doesn’t equal low corruption. I got pulled over in a friend’s car after paying the toll ($1.50) for the Katembe bridge, and the police officers asked both of us (addressing my friend in Xitsonga) for help paying for food. This happened again on a highway to Matola. My Mozambican friends all told me that these road checkpoints are very new, because control of road policing had shifted from the city to national police last month. One secretary to a government official told me that she was “very hungry,” and my meeting would start sooner if I helped her with lunch. Each time, it was easy to politely decline to pay the bribe. The x-ray operator at the airport, on my flight out, also told me, “I’m very hungry. Can you help me?” I remembered that I had 90 metical ($1.35) in my pocket that I had to get rid of, and offered it to him. He looked like he thought he was on candid camera, and quickly explained he had been joking. It seemed that no one had ever taken him up on this before.

There is a good amount of interesting architecture in the city.

Tyler Cowen once put this book on his annual list of favorite non-fiction. I haven’t splurged on it yet, but there are definitely Maputo buildings which I could imagine being in there, unlike Freetown or Kanifing.

Even the average street in the older part of the city is attractive, in part due to the abundance of acacia trees and the wide avenues. But there’s also a lot of remaining attractive colonial-era architecture between the soviet-style apartment blocks.7

Because of low traffic, trees, and wide avenues, Maputo’s streets are the quietest I’ve encountered in poor countries. In Kolkata and Freetown, the streets are so narrow and crowded that one horn will propagate and echo. To make up for its quiet, Mozambique is incredibly loud in social and common spaces. At an open-mic night at the Associação dos Músicos Moçambicanos, the speakers were placed so close to the small crowd that my beer jumped with the bass. I got my first taste of vuvuzelas since 2010 not at the Mozambique-Guinea World Cup Qualifier, but walking past a political rally. Santa Maria beach on Inhaca Island was the most isolated and quiet beach I’ve ever visited, until some Mozambicans offloaded a 3-foot tall, $2,000 speaker and blasted dance music. No one danced.

Besides this, the social scene in Maputo is pretty laid-back and a lot of fun. Middle- and upper-class restaurants and clubs are very well integrated, which is rare in West Africa. The expat community isn’t as separated from the wealthier locals, and even at very cheap restaurants in poor neighborhoods there were white Portuguese. Proximity to South Africa probably plays a part in this.

Getting around

Yango is the local ride-hailing app and makes life really easy. It’s a Dubai-based company, split off from Russian Yandex in 2024. Today it’s available as a ride-hailing app in 30+ African countries. Yango rides are really cheap, cheaper than taxis in Freetown or Kanifing, and quality was much higher. A 15 minute ride from my house to my office cost $0.23 on a motorbike, $0.58 in a tuk-tuk, $1.05 in a car, and $1.20 in the equivalent of an Uber Black car. I usually ended up taking the cheaper car option, because you can’t easily sit next to or talk to the driver of a tuk-tuk.

Yango eliminates the ability of taxi drivers to price discriminate. When I walked out of the airport, the taxi drivers wanted ~$20 for the drive to my flat, and I talked them down to $10. On Yango, the drive is $3. My general model of digital marketplaces is that they enable price discrimination (e.g., Uber surge pricing), but in Mozambique it’s the opposite.

Drivers are often professionals working a full-time job, or graduate students. I met a dentist, an engineer working at the new Total plant, several accountants. They also made up the majority of the Muslim Mozambicans whom I met. Most Muslims in Maputo are first- or second-generation immigrants from the northern provinces. One driver, Ismael, grew up on Mozambique Island, about 1,000km north of Maputo; it has a population of 10,000, but most of the young people move to Maputo. He came down to study engineering and now works at a terminal exporting natural gas.

Because I wasn’t on the local mobile money system, I paid for each Yango ride in cash. The car drivers rarely had change (tuk-tuk drivers always did). Alongside rating the driver in the Yango app out of 5 stars, you have to reply yes/no to the question “Did the driver ask for extra cash?” This led to the drivers being very reluctant whenever I told them to keep the change, even when I showed them I had already selected “no”. So we often went around to fruit sellers asking if they would break a twenty.

Food

The amount of good food, London-quality food in Maputo is surprising. If you’re visiting Maputo, you can reach out for a list of restaurants, as restaurant quality isn’t very correlated with reviews on Google or Facebook. I’d say Lumma was highest quality preparation and presentation,8 the Maputo fish market was best quality ingredients, and it’s impossible to choose best quality for money, because of the $1.50 beef, chicken, and fish dishes prolifically available on street corners. I cooked for myself much less here than in Gambia or Sierra Leone because of the lower prices at nicer restaurants, and the good quality of street food.

Inputs are just really cheap, and that makes food cheaper across the income distribution. One directly comparable setting: I visited the IGC Maputo offices during a training session for enumerators on a property tax project. Back in 2021, when I worked for IGC Sierra Leone, we held a comparable training for the same number of enumerators and same type of project. There, we didn’t pay for their breakfast, and we got them egg sandwiches for lunch. In Maputo, the IGC enumerators got sliders, cake, and a fruit platter for breakfast, and four hot dishes (two chicken, one beef, one fish) for lunch. This is especially surprising given the salary to enumerators is slightly lower in Mozambique: $150 per month, compared to (best memory) $200 in Sierra Leone.

There’s an abundance of beef, mostly imported from South Africa and Zimbabwe. I visited an abattoir north-west of the city, relatively small-scale, which processed in the low-hundreds of cattle per day. Most of it is low quality and hamburgers are an available splurge even in the poorest neighborhoods. Despite this, there is absolutely no dairy. The supermarkets have that horrible shelf-stable milk, which I drank because I love milk, but there were no local options for milk, cheese, yogurt.

The supermarkets were impressive; I put this down to the large Portuguese community. The two I visited were the size of American Targets; they sold bikes, leafblowers, and Christmas trees besides. There are at least two more that I didn’t visit, and they’re not part of a chain. There was nothing of this scale in Sierra Leone or Gambia.

What to do

Go to the beach

I joined a “Maputo expats” Whatsapp group before I arrived. The most common message, every Thursday evening, is “Hello! Is anyone going to Ponta this weekend? Two seats please; happy to chip in for gas.”

Ponta do Ouro is a beach town a couple hours south of Maputo. Until the Katembe bridge was finished in 2020, it required a slow, unpleasant ferry ride across the bay, or a seven hour detour. Now, the number of resorts and dive schools has exploded.

I didn’t get a chance to visit Ponta, but we did take a day boat trip across Maputo Bay to Inhaca and Portuguese Islands. Besides the loud music following us everywhere, these beaches were isolated and very beautiful.

Night life

As I said: loud, so bring earplugs. I wore my airpods on noise-reducing to one live concert. Also, things start earlier in the evening than you’d expect, perhaps because of the timezone.

Visit Mafalala

The Mafalala district is just north of central Maputo, just north of the old ring road built to separate the black suburbs from the Portuguese white city center. It’s a poor barrio; from satellite view, most roofs look like aluminum siding. But it’s seen heavy investment. The main roads are all newly paved with brick, and many of the drainage ditches which should have been dirty streams are now dirty concrete. A big part of this is historical personae and independence mythos: Samora Machel was born there, as was Eusébio, the most famous Mozambican footballer.

The level of infrastructure investment seems massively disproportionate to the history. Best I can tell, most of this is due to a tourism and community-building organization founded in 2009. IVERCA has also been remarkably successful at drawing fundraising for community projects — football pitches, affordable housing, and urban planning from the Danish government; World Bank and UN-Habitat for road and drainage improvements; the EU and German delegations funding a museum and backpacker’s hostel. Best I can tell, none of these would have happened without IVERCA.9

The museum is IVERCA’s crown jewel. It’s a very cool building, located at the highest point in the swampy neighborhood and by far the most colorful entry. The hostel is above the museum, and has two remarkable rooms hidden away in attics. I would recommend the place to stay for a night, but note it is not convenient to any other part of the city, and very difficult to get taxis or tuk tuks out of. The neighborhood is fun to walk around during the day.

There are many further proposals for development of Mafalala. The Danes have partnered with IVERCA and urban planning firms to design health centers, libraries, and community centers, but the museum docent told us none of that is funded yet. The most obviously missing part of the neighborhood was any type of commercial development: there were no markets or shops besides fast food stalls. The residents mostly commute into central Maputo.

Go to a soccer game

I went to the World Cup qualifiers, Guinea vs. Mozambique, at the Zimpeto National Stadium. The stadium is about ten miles north of the city, in a large dusty field next to a relatively new four lane highway. It’s large — at 42k seats, real, plastic seats in the colors of the flag, not bleachers, and built by the Anhui Foreign Economic Construction Group in 2011. Besides a brutalist clocktower on the south end and the colorful seats, there is nothing fancy about the stadium. The scoreboards on either end could only display the score, not a clock, and one-fifth of the pixels were out.

I went with a GIZ consultant on his first trip to Africa, and his first time at a football match outside of Europe. The first surprise came as we approached the steps to the main gate: Guinea scored in the second minute, and the crowd of Mozambicans still arriving heard the cheers, shoved forward, and pushed over the fences around the turnstiles.

I’ve been to soccer games in Sierra Leone and Gambia, in Afghanistan, and, once, to an A’s-Giants game at the Oakland Coliseum. This was probably the most chaotic venue I’ve been to. The ~$2 we spent on tickets was wasted; no one ever looked at them.

The guys sitting next to us really wanted us to stay sitting next to them. At the half, Laurin and I walked around the concourse eating cashew nuts. From 50 meters up the pitch, we could see these ten guys, with their hands up, hissing into the wind at us, to make sure we saw them and could find our way back. Maybe we’re good luck.

We weren’t. After Mozambique tied it at 1-1, Guinea went ahead early in the second half and Mozambique couldn’t do anything for the rest of the match. There were epic levels of shithoussery. Mozambique had a particularly dangerous freekick, the Guinean manager went for a substitution just before, but the player took so long coming off the field (despite his best efforts! an assistant manager shoved him back over the line onto the field several times to delay play) that the official cancelled the substitution. At another point, the keeper passed back and forth to a midfielder three times, just for fun.

Other notes

Mozambique shares a timezone with all the other Southern African countries. As the easternmost country in the timezone, this feels really weird! When I arrived, sunrise was at 5:20am, and sunset about 12 hours later. The early sunsets move business and social events earlier throughout the day. I’m a morning person, but it would usually be considered rude to suggest a 7am in-person meeting. Not here!

The Kalashnikov is a prominent national symbol in Mozambique; it’s on the flag. In particularly touristy areas, hawkers would try to sell me flags, jerseys, banners, scarves with ever-larger AK-47s on them.

I visited the Honen Dalim synagogue in Maputo for Kabbalat Shabbat. They only ever have a minyan during the high holidays, but we got together five jews for this Friday night. It’s a very cool building, and much more fun than visiting Chabad. They’re looking for a rabbi!

Cash is very annoying here, but that’s everywhere in Africa. While there are ATMs everywhere in the city, the three at the airport were all not working when I landed. I joined a line of six shamefaced white people trooping back to the moneychangers we had so confidently brushed off on our way to the ATMs. It is very difficult to get small bills, and this is annoying, and no one has change. I bluffed my way into stacks of 20 metical notes at a few banks, but they don’t last long. Merchants and Yango drivers are just as eager to get their hands on them. If you have a 20 metical note, they won’t give you change even if they have it.

The roads and sidewalks are really good; every road in Maputo is paved (not close to true in Freetown or Kanifing!). But there are a lot of sudden deep holes in the sidewalk. This is because manhole covers are stolen and sold for scrap, according to a police officer.

Outside the airport, there was a big Vodacom billboard saying, “It’s simple to get an eSIM.” It is not simple to get an eSIM. To activate the eSIM you need to first insert a physical SIM. My 2025 iPhone 16e doesn’t even have a SIM slot, which was verified by a dozen Vodacom employees at three stores. They all reacted with shock.

Format and style cribbed from Matt Lakeman, whose notes on Gambia and Sierra Leone I endorse. I’ll be making a lot of comparisons to Freetown and Kanifing throughout this piece.

We have a ton of detail about what was going on in e.g., Aden 3,000 years ago, but nothing in Maputo until 500 years ago. This is kind of a bummer.

In the chaos, Portugal also granted East Timor independence; it was promptly invaded by Indonesia. They tried to give back Macau, but China said no. Portugal retained Macau until 1999.

Optimist Party for the Development of Mozambique.

This stands for National Alliance for a Free and Autonomous Mozambique, but more controversially the initialism means “it’s over” in Macua. The FRELIMO government blocked the new name, and it might be changed to ANAMOLA.

Some of these apartment buildings reminded me most of Astana.

We were really impressed with the seafood mains and tapas we got. Half the price of London, better quality inputs, equal presentation. The three desserts we tried were all bad.

Named after the three founders: Ivan, Erica, Carlos.

great read. I was interested by your comment "Mozambique also feels richer than Gambia, which is twice as rich per capita!"

I travelled to Rwanda and Nigeria recently, and observed the eaxct same phenomonom. Nigeria GDP per capita is 2x, but Rwanda FEELS righer. For example, the median car in rwanda would be among the nicest cars you see all day in Nigeria, but the median car in Nigeria would not be on the road in Rwanda. Similarly, an airport in Rwanda feels organised while Nigeria it is chaos.

This confused me becuase my experience travelling outside africa is that relative wealth of an area is pretty easy to guage accurately.

> The x-ray operator at the airport, on my flight out, also told me, “I’m very hungry. Can you help me?” I remembered that I had 90 metical ($1.35) in my pocket that I had to get rid of, and offered it to him. He looked like he thought he was on candid camera, and quickly explained he had been joking. It seemed that no one had ever taken him up on this before.

I laughed out loud.

> But there are a lot of sudden deep holes in the sidewalk. This is because manhole covers are stolen and sold for scrap, according to a police officer.

I've noticed the missing metal covers for street infrastructure thing in other developing countries as well (like Mexico). Never understood why, so thanks for this!